What Was the Arkenstone?

A Mineralogical Investigation of the Heart of the Mountain

Written by Ian Gubbenet

Co-written by Nimue Avallon (Art and Geological consultation)

Note: Image for Figure 1 generated by ChatGPT

Tolkien never tells us what the Arkenstone actually is. In The Hobbit, we learn that during Thráin I’s reign, as Erebor was established, the Dwarves found “a great white gem” deep beneath the roots of the Mountain. Not at the summit, but in its ancient bones. The Dwarves fashioned it into a globe with a thousand facets. In darkness it glimmered pale; under light, it blazed white with rainbow glints shooting through its depths. They called it the Heart of the Mountain.

When the Dwarves discuss the treasures lying beneath Smaug’s guard, Tolkien describes it: “But fairest of all was the great white gem, which the dwarves had found beneath the roots of the Mountain, the Heart of the Mountain, the Arkenstone of Thrain.”

Thorin obsesses over it in the darkness: “’The Arkenstone! The Arkenstone!’ murmured Thorin in the dark, half dreaming with his chin upon his knees. ‘It was like a globe with a thousand facets; it shone like silver in the firelight, like water in the sun, like snow under the stars, like rain upon the Moon!’”

When Bilbo discovers it atop Smaug’s hoard, Tolkien gives us the stone’s most detailed description:

It was the Arkenstone, the Heart of the Mountain. So Bilbo guessed from Thorin’s description; but indeed there could not be two such gems, even in so marvellous a hoard, even in all the world. Ever as he climbed, the same white gleam had shone before him and drawn his feet towards it. Slowly it grew to a little globe of pallid light. Now as he came near, it was tinged with a flickering sparkle of many colours at the surface, reflected and splintered from the wavering light of his torch. At last he looked down upon it, and he caught his breath. The great jewel shone before his feet of its own inner light, and yet, cut and fashioned by the dwarves, who had dug it from the heart of the mountain long ago, it took all light that fell upon it and changed it into ten thousand sparks of white radiance shot with glints of the rainbow.

When Bilbo lifts it, his reaction tells us its size: “Suddenly Bilbo’s arm went towards it drawn by its enchantment. His small hand would not close about it for it was a large and heavy gem.”

That’s everything canon gives us. No mineral name. Tolkien describes what it looked like, what it did to light, what it did to those who saw it, and how large it was. Nothing about what it actually was.

The Question Nobody Asks

Tolkien scholarship reasonably treats the Arkenstone as symbol rather than substance. It sits in that constellation of radiant objects (the Silmarils, the Arkenstone, the Ring) that trace the corruption bright things work on hearts. The emphasis falls on meaning: kingship, inheritance, dragon-sickness. What the stone actually was hardly matters to that reading.

But treating Middle-earth as coherent prehistory means Tolkien’s descriptions become physical constraints, not just metaphors. If we ask what rock could produce these specific effects, we’re stepping from literary analysis into geology.

We need a mineral that appears as “the great white gem” but throws rainbow fire. That appeared as “a little globe of pallid light” in darkness, shining “of its own inner light,” yet took “all light that fell upon it and changed it into ten thousand sparks of white radiance shot with glints of the rainbow.” That shone “like silver in the firelight, like water in the sun, like snow under the stars, like rain upon the Moon.” That can hold an extreme polish on a hand-sized faceted sphere too large for a hobbit’s hand to close around, softball-sized. That forms deep within mountains through volcanic or hydrothermal processes. That’s durable enough to survive Dwarven cutting, centuries in a dragon’s hoard, siege, and funeral pyre.

Few candidates meet these requirements.

The Geological Brief

Start with provenance. The Arkenstone came from deep beneath Erebor (”the dwarves had found [it] beneath the roots of the Mountain”), and treating Middle-earth’s isolated peaks as volcanic in origin makes geological sense. That gives us a hydrothermal environment: superheated water circulating through fractured rock, depositing minerals as it cools. This is how mountains build their treasure chambers. Quartz veins, opal deposits, the slow accretion of dissolved silica into crystalline form.

The thousands of years between Erebor’s volcanic formation and Thráin I’s reign (circa 4,900 BCE by NOME chronology, which maps Tolkien’s Ages onto real-world prehistory) would allow ample time for such hybrid silica structures to develop in deep hydrothermal systems. My NOME Timeline framework places the Third Age at 7,022 to 4,001 BCE, corresponding to the Chalcolithic period, giving us a real-world geological context for what processes might have created such a stone.

Now add optics. Tolkien’s description demands both body color and spectacular light behavior. The stone appeared milky white (”the great white gem”) but transformed under illumination into rainbow fire. The “own inner light” effect suggests either exceptional clarity allowing ambient light to gather and concentrate, or play-of-color from internal structure. The “thousand facets” tell us the Dwarves cut it into a densely faceted sphere, which means the base material had to survive extreme mechanical stress during grinding and polishing.

The base material scatters or reflects light to appear milky, while internal structure or high refractive index breaks white light into spectral colors. In dimness, it appeared to glow from within (not true luminescence, but the way certain stones gather and hold ambient light). Under direct illumination, it exploded into “ten thousand sparks of white radiance shot with glints of the rainbow.”

Finally, mechanics. A thousand facets on a sphere 95-100mm in diameter (softball-sized, since a hobbit’s small hand couldn’t close around it) means intricate grinding and polishing. The spherical form itself is optimal: it distributes internal stress evenly, minimizes the risk of fracture propagation, and maximizes light gathering from all angles. The stone must be hard enough to take that treatment without crumbling, tough enough to resist impact and thermal shock, stable enough not to crack or craze over centuries. We’re talking Mohs hardness of at least 6.5, preferably 7 or higher, for long-term facet retention.

Why Not Diamond?

The optical case for diamond is perfect. Maximum brilliance, strong dispersion for those rainbow flashes, facets that stay sharp. But geology kills it. Diamonds crystallize in kimberlite pipes from deep mantle conditions: pressures and temperatures that have nothing to do with volcanic mountains. And a flawless diamond the size of a softball exists nowhere outside fantasy.

Why Not Pure Opal?

Opal seems ideal. It forms readily in volcanic systems through hydrothermal silica precipitation. Its play-of-color (that internal fire) matches Tolkien’s “rainbow glints” perfectly. The white or crystal varieties give us the milky body and could explain the apparent “own inner light” as concentrated play-of-color.

But opal is hydrated silica: it contains 3 to 10 percent water trapped in its structure. This makes it relatively soft (5.5 to 6.5 on Mohs scale) and prone to crazing as it ages and loses moisture. Thermal cycling makes it worse. A pure opal sphere with a thousand facets, subjected to the intermittent temperature swings of a dragon’s hoard and the handling of adventurers, would almost certainly develop networks of fine cracks. The larger the piece, the more unstable. At softball size with intricate faceting, pure opal won’t survive.

The Other Candidates

Colorless beryl (goshenite), topaz, and zircon represent interesting middle ground. All three are hard and facet-friendly minerals. Zircon especially has strong dispersion rivaling diamond for rainbow fire. But large, flawless specimens are extraordinarily rare, and their geological occurrence leans toward pegmatites and specialized hydrothermal pockets rather than the heart of volcanic systems. Zircon also suffers from metamictization (radiation damage causing brittleness) in older specimens. They’re possible if we allow for a once-in-an-age crystal, but they stretch probability.

The softer options fail outright. Moonstone (adularia) has that attractive blue sheen, selenite offers pearly glow, fluorite and calcite can show fluorescence or phosphorescence. All have optical charm, but they’re too soft or too prone to cleavage to survive being ground into a densely faceted sphere that gets handled across centuries. A king-jewel needs durability as much as beauty.

No single known mineral satisfies all constraints without a composite structure.

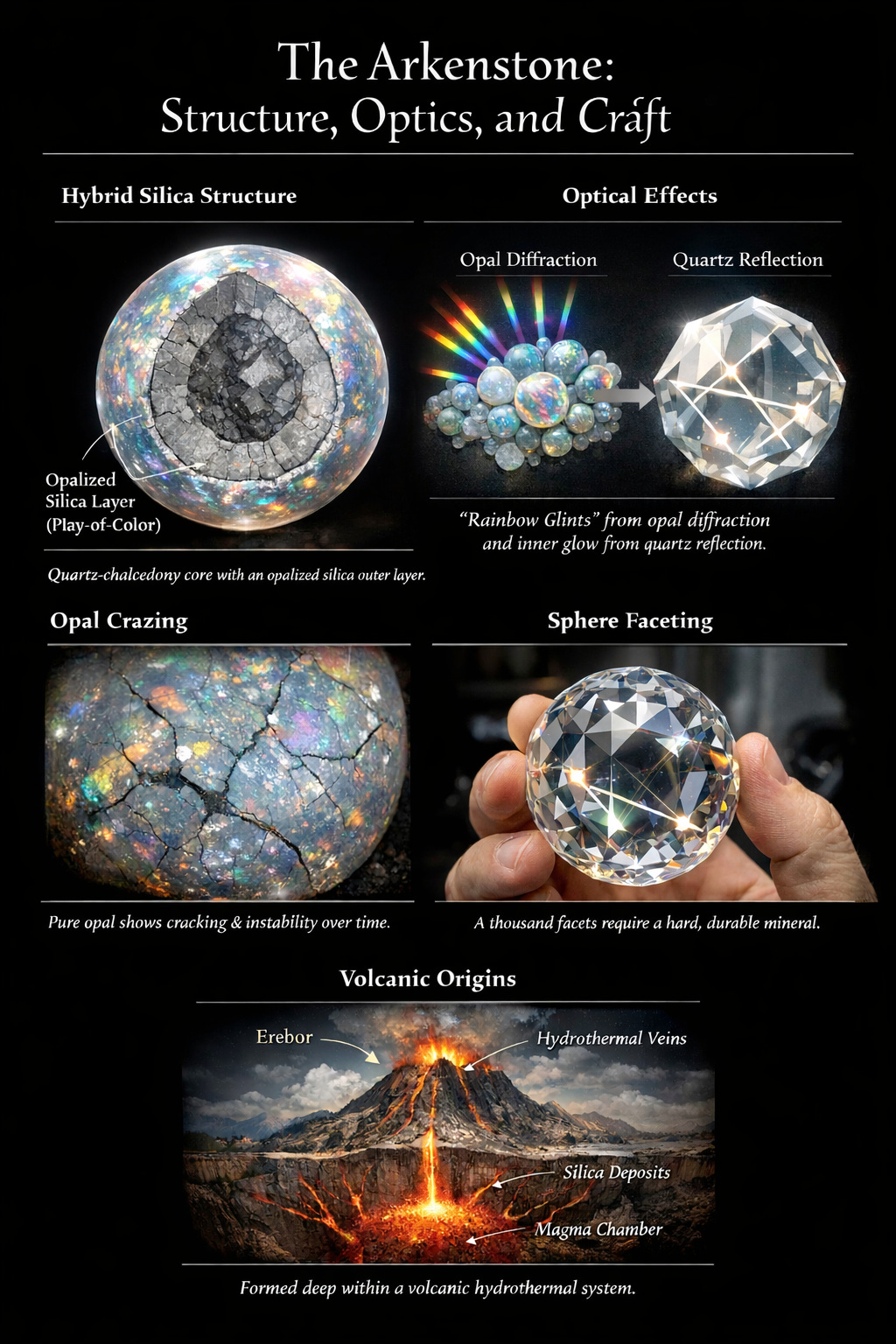

The Hybrid Solution

Nimue Avallon’s geological instinct proved decisive. She suggested looking at hydrated white opal, recognizing that opal’s volcanic provenance and optical properties matched the text, though the mechanical problems remained. The solution lies in what nature sometimes does: opalized silica structures, where opal precipitates around or replaces more stable silica cores.

Picture a quartz or chalcedony skeleton (hard, tough, geologically stable) with an opal-rich surface layer. The core provides structural integrity; the outer layer provides the optical fireworks. This isn’t speculative; such composite structures exist in nature wherever silica-rich fluids permeate existing crystals or where opal formation occurs in layers.

The Arkenstone would be this hybrid silica structure taken to its extreme: a massive quartz-chalcedony core with significant opal in its outer layers, allowing Dwarven craftsmen to expose the play-of-color through strategic faceting while keeping the structural stability of the harder silica beneath.

Ancient Dwarven technique could potentially push such a stone beyond what modern lapidaries typically attempt. The cutting itself presents no technical barrier: hand tools (hammer, chisel, abrasives) work slower and cooler than modern grinding machines, generating less thermal stress and allowing the craftsman to stop instantly if the stone responds wrong. Modern faceting machines create continuous friction between stone and lap, building heat that can activate non-visible fractures in the crystal structure. For a hybrid structure with opal layers (particularly vulnerable to thermal cycling and vibration), hand-cutting would be gentler. A modern master lapidary could replicate the Dwarven approach given sufficient time and funding, but economic reality makes multi-year hand-faceting projects uncommercial.

The Dwarven advantage lay not in the tools but in time and technique. Between cutting sessions, they may have applied low-frequency acoustic treatment. Research on metals shows that vibration at 30 to 100 Hz during fabrication refines grain structure and reduces residual stress through dislocation movement in the crystal lattice. Dwarven voices would sit naturally in this range: their anatomy (shorter stature, thicker vocal cords than Men or Hobbits) would produce fundamental frequencies perhaps 40 to 100 Hz, lower than human speech. Deep chanting at resonant frequencies could relax the stone’s internal tensions between cutting sessions without causing destructive resonance. This technique, if it existed, has not survived in modern lapidary practice. No evidence exists that such techniques were ever applied to silicate minerals; the comparison is offered as a conceptual analogy rather than a documented lapidary practice.

The lore supports this reading. The Dwarves worked stone through song and understood how mountains rang under the hammer. This wasn’t poetry, it was technique. They knew which tones steadied the stone and which would shatter it. Combined with methods to stabilize water content in the opal layers, controlled annealing to heal micro-fractures, and the luxury of time measured in years rather than billing hours, such craft could achieve what modern economics discourages: a softball-sized, densely faceted sphere of hybrid silica that survived millennia without crazing or fracture.

The “own inner light” effect comes from two sources. The dense quartz core, with its high optical clarity, gathers and concentrates ambient light even in near-darkness, creating that “little globe of pallid light” Bilbo saw from a distance. The opal layers, when activated by torch-light or direct illumination, explode into play-of-color: those “ten thousand sparks of white radiance shot with glints of the rainbow.”

Geologist’s Note: A softball-sized, micro-faceted pure opal sphere is impossible with known materials. But a hybrid silica structure (opal-rich surface on a quartz or chalcedony core) could deliver opal’s fireworks with quartz’s backbone, especially if ancient Dwarven craft included techniques to stabilize water content and heal micro-fractures during cutting and annealing. That’s the most believable route to Tolkien’s optics, shape, and durability in a single stone.

This also explains why the stone was the Heart of the Mountain rather than merely treasure. Most volcanic systems that produce opal don’t simultaneously create hand-sized quartz cores with this hybrid silica structure. Finding both qualities in one stone would be geologically extraordinary even by the standards of rare gems. “Indeed there could not be two such gems, even in so marvellous a hoard, even in all the world.”

What About Quartz Alone?

Pure rock crystal (clear to milky quartz) remains the most physically realistic candidate. It grows enormous in hydrothermal environments. It’s hard (7 on Mohs), tough, and stable. It takes intricate faceting and mirror polish beautifully. And at softball size, such crystals, while rare, actually exist in nature.

The weakness is optical subtlety. Quartz satisfies geology better than it satisfies Tolkien’s optics. It has modest dispersion compared to diamond or even opal’s play-of-color. It can be brilliant, especially with careful faceting, but it doesn’t naturally produce dramatic rainbow fire unless internal structure helps: aligned fluid inclusions, subtle phantoms, or crystallographic orientation that enhances light scatter.

If Tolkien meant something less magical than the text suggests, rock crystal works. But “like rain upon the Moon” and the “ten thousand sparks” and that sense of inner fire push toward something more optically active.

Could We Make One?

With rock crystal or lab-grown quartz, yes, and rather easily. Crystal spheres 95 to 100mm in diameter are commercially available. Modern CNC equipment with indexed jigs can facet a sphere with hundreds to over a thousand micro-facets. Progressive polishing with diamond compounds, finishing with cerium oxide, produces optical-quality surfaces. Mount it on a minimal cradle, light it carefully to maximize apparent inner glow, and you’d have something striking.

A high-quality rock crystal sphere in that size range typically costs between $300 and $1,200 depending on clarity (current market estimates). The precision faceting work would add significantly to the price, likely bringing the total to $3,000 to $7,000 for a skilled lapidary working on commission. Lab sapphire would be even more durable, though considerably more expensive at perhaps $15,000 to $25,000 for the complete piece. Fused silica or optical glass machines most easily of all.

Creating the hybrid opal-over-quartz structure would be the real challenge. You’d need to grow or bond the layers, then risk the entire assembly on faceting operations that might crack the opal veneer. Possible in theory, treacherous in practice.

The impossible options? Pure opal, moonstone, fluorite, calcite, or selenite at that size and finish. Their softness, cleavage planes, and hydration issues defeat the concept before you begin.

Note: This section discusses modern reproduction as a thought experiment in material limits, not as interpretation of Tolkien’s text. The Arkenstone’s canonical nature remains what the previous analysis proposes: a geologically plausible hybrid silica formation.

The Heart of the Mountain

The Arkenstone exists at the intersection of geology and craft. Physically, it’s most plausibly a volcanic silica giant: white opal character riding a quartz-chalcedony backbone, a once-in-an-age formation brought to perfection by hands that understood stone at depths we’ve forgotten.

But its real nature is what it does to the hearts around it. Thorin says “it is beyond price” and would rather die than surrender it. Bilbo risks everything to break the siege with it, giving it to Bard despite knowing Thorin’s rage would follow: “This is the Arkenstone of Thrain,” said Bilbo, “the Heart of the Mountain; and it is also the heart of Thorin. He values it above a river of gold.”

Making it real makes the obsession more terrible. Men have killed for far lesser stones.

Still, if you found yourself deep beneath a mountain, in some ancient cavity where superheated water once ran, and you discovered “the great white gem” with milky fire in its heart, you’d know it. That kind of beauty announces itself. You’d understand why it drew Bilbo’s feet toward its pale gleam in the darkness, why “there could not be two such gems, even in so marvellous a hoard, even in all the world.”

References

Primary Sources

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937). The Hobbit, or There and Back Again. George Allen & Unwin.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (2012). The Hobbit (75th anniversary ed.). HarperCollins.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien (H. Carpenter & C. Tolkien, Eds.). Houghton Mifflin.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (2023). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded Edition (H. Carpenter, C. Tolkien, & W. G. Hammond, Eds.). HarperCollins.

Tolkien Scholarship

Flieger, V. (2014). The jewels, the stone, the ring, and the making of meaning. In J. Wm. Houghton et al. (Eds.), Tolkien in the New Century (pp. 65–77). McFarland.

Scull, C., & Hammond, W. G. (2017). The J. R. R. Tolkien Companion and Guide: Reader’s Guide (rev. ed.). HarperCollins.

Hammond, W. G., & Scull, C. (2006). The Lord of the Rings: A Reader’s Companion. HarperCollins.

Shippey, T. A. (2000). J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins.

Lehoucq, R., Mangin, L., & Steyer, J.-S. (Eds.). (2021). The Science of Middle-Earth: A New Understanding of Tolkien and His World. Pegasus Books.

Mineralogy and Gemology

Deer, W. A., Howie, R. A., & Zussman, J. (2013). An Introduction to the Rock-Forming Minerals (3rd ed.). Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

Gaines, R. V., Skinner, H. C. W., Foord, E. E., Mason, B., & Rosenzweig, A. (1997). Dana’s New Mineralogy: The System of Mineralogy of James Dwight Dana and Edward Salisbury Dana (8th ed.). Wiley.

Nassau, K. (1983). The Physics and Chemistry of Color: The Fifteen Causes of Color. Wiley-Interscience.

O’Donoghue, M., & Joyner, L. (2003). Identification of Gemstones. Butterworth-Heinemann.

Read, P. G. (2005). Gemmology (3rd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann.

Sinkankas, J. (1994). Gemstone & Mineral Data Book. Geoscience Press.

Webster, R., & Read, P. G. (Eds.). (2000). Gems: Their Sources, Descriptions and Identification (5th ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann.

Opal Formation and Characteristics

Graetsch, H. (1994). Structural characteristics of opaline and microcrystalline silica minerals. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, 29(1), 209–232.

Jones, J. B., & Segnit, E. R. (1971). The nature of opal I. Nomenclature and constituent phases. Journal of the Geological Society of Australia, 18(1), 57–68.

Lyndon Jones, J., & Segnit, E. R. (1972). Genesis of cristobalite and tridymite at low temperature. Journal of the Geological Society of Australia, 18(4), 419–422.

Sanders, J. V. (1968). Diffraction of light by opals. Acta Crystallographica Section A, 24(4), 427–434.

Hydrothermal Systems and Volcanic Mineralogy

Fournier, R. O. (1999). Hydrothermal processes related to movement of fluid from plastic into brittle rock in the magmatic-epithermal environment. Economic Geology, 94(8), 1193–1211.

Hedenquist, J. W., & Lowenstern, J. B. (1994). The role of magmas in the formation of hydrothermal ore deposits. Nature, 370(6490), 519–527.

Simmons, S. F., & Browne, P. R. L. (2000). Hydrothermal minerals and precious metals in the Broadlands-Ohaaki geothermal system: Implications for understanding low-sulfidation epithermal environments. Economic Geology, 95(5), 971–999.

White, D. E., & Waring, G. A. (1963). Volcanic emanations. In Data of Geochemistry (6th ed., Chapter K). US Geological Survey Professional Paper 440-K.

Lapidary and Gemstone Processing

Federman, D., & Hammid, T. (1990). Consumer Guide to Colored Gemstones. Bonus Books.

Kraus, P. D., & Slawson, C. B. (1947). Gems and Gem Materials (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Sinkankas, J. (1984). Gemstone Carving: Materials, Techniques, and Gallery of Gemstone Carvings. Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Vargas, G., & Vargas, M. (2004). Faceting for Amateurs (2nd ed.). Privately published.

Vibratory Stress Relief and Material Processing

Dawson, R., & Moffat, D. G. (1980). Vibratory stress relief: A fundamental study of its effectiveness. Journal of Engineering Materials and Technology, 102(2), 169–176.

Shalvandi, M., Hojjat, Y., Abdullah, A., Asadi, H., & Gholipour, J. (2013). Influence of ultrasonic stress relief on stainless steel 316 specimens: A comparison with thermal stress relief. Materials & Design, 46, 713–723.

Tamasgavabari, R., Ebrahimi, A. R., Ghambari, M., & Honarpisheh, M. (2020). Strength and fatigue crack growth behaviours of metal inert gas AA5083-H116 welded joints under in-process vibrational treatment. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 772, 138798.

Tewari, S. P., Shanker, P., & Pandey, O. P. (2020). Impact of low frequency vibration during welding and annealing on microstructure of mild steel butt-welded joints. Lupine Publishers: Materials Science Journal, 4(4), MS.ID.000162.

I found this entire article to be fascinating reading. Bravo!

I loved this. Didn’t know I needed it til I started reading it. Well done.